Figure Skating in the Formative Years: Singles, Pairs, and the Expanding Role of Women

Figure Skating in the Formative Years: Singles, Pairs, and the Expanding Role of Women

Contents

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Mythology and the Earliest Skaters Mythology and the Earliest Skaters

-

The Earliest Skates The Earliest Skates

-

An Early Account of Recreational Skating An Early Account of Recreational Skating

-

Skating as a Tool of Warfare Skating as a Tool of Warfare

-

The Dutch Roll The Dutch Roll

-

Skating’s Patron Saint Skating’s Patron Saint

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Cite

Abstract

Today, skating on artificial ice in indoor rinks is a year-round recreational activity enjoyed by people of all ages and abilities as well as a sport both amateur and professional that enjoys unprecedented popularity. But throughout most of its history, ice skating has been an activity limited to short seasons and possible only in countries where lakes, ponds, canals, or other bodies of water provide frozen surfaces on which skaters could enjoy the challenge and excitement of gliding across natural ice. In the ancient world, long before skating became a recreational activity or a sport, those same frozen surfaces provided a different kind of challenge. Passage over them was a necessity for survival during harsh winter months. This chapter traces the history of ice skating before the advent of competitive figure skating. It discusses mythology and the earliest skaters; the earliest skates; an early account of recreational skating; skating as a tool of warfare; figure skating's patron saint, the virgin Lydwina of Schiedam.

skating on artificial ice in indoor rinks is today a year-round recreational activity enjoyed by people of all ages and abilities as well as a sport both amateur and professional that enjoys unprecedented popularity. But throughout most of its history, ice skating has been an activity limited to short seasons and possible only in countries where lakes, ponds, canals, or other bodies of water provide frozen surfaces on which skaters could enjoy the challenge and excitement of gliding across natural ice.

In the ancient world, long before skating became a recreational activity or a sport, those same frozen surfaces provided a different kind of challenge. Passage over them was a necessity for survival during harsh winter months. Snowshoes, skis, skates, and sledges evolved early as practical means of travel over the frozen landscape. But whether as a means of transportation in ancient times or as a recreational activity in the modern world, skating outdoors has always provided practitioners with an exhilarating experience of rapid movement, with cool winter air blowing on their faces. Brian Boitano expressed it well following the filming of Water Fountain in Alaska when he said, “Skating on the lake in Alaska was probably one of my dreams come true. I can truthfully say that … it was the closest I’ve come to being so touched that I cried in a skating performance.”1Close

Today, competitive skating is done indoors under controlled conditions, certainly an advantage in the highly competitive world of figure skating. No longer must skaters concern themselves with the hazards of natural ice, with adjustments for wind conditions affecting all aspects of their programs, or with the biting cold temperatures that can adversely affect performance, but those hazards were reality and part of the challenge for competitive skaters until 1966, when the last major outdoor figure skating competition, the World Championships, was held at Davos, Switzerland.2Close It is unlikely that any contemporary skater would choose to return to those former conditions, but something was lost when skating moved indoors. Many former skaters fondly remember competing on outdoor ice. “What I loved most was the sheer joy of skating, natural ice that gave jumps their spring, flowing movements, and deep edges, vibrant skies, and glorious mountains, all of which lifted my spirits,” reminisced Olympic champion Dick Button in 1990.3Close

Skating has developed into three disciplines, speed skating, ice hockey, and figure skating, all of which are practiced both on ice skates and roller skates. Indeed, the histories of skating on blades and rollers have parallel developments. Ice skating has a longer history and is today more popular, particularly at the competitive and professional level, but at times skating on rollers, first developed in the nineteenth century, has been as popular as skating on blades. Roller skates were invented to provide year-round skating in the days before artificial ice, and their popularity surpassed all expectations. The public filled roller rinks, and some early skaters competed successfully in both arenas. This history, however, deals only with figure skating on blades.

Mythology and the Earliest Skaters

A history of figure skating must begin with myths from Scandinavian countries, stories that provide the earliest accounts of movement on ice in the ancient world and tell us about skating’s earliest practitioners. Although none were committed to writing before the twelfth century, they recount stories from much earlier times. Some may date back as far as the Scandinavian Bronze Age, which lasted for more than a thousand years, beginning about 1600 b.c., but because no written sources survive from that period, we must rely on archeological evidence for our somewhat limited knowledge. Identifiable gods and goddesses associated with skating appear early, but their history remains obscure until the period of migration, beginning about 300 a.d.

Written sources for northern myths are by two Christian writers, Saxo Grammaticus, a twelfth-century Dane, and Snorri Sturluson, a thirteenth-century Icelander. They recount stories that had long been in oral tradition. It is from Snorri, a brilliant poet, historian, and politician whose Prose Edda dates from about 1220, that we gain most of our knowledge about the gods themselves. Saxo preserved many tales in his lengthy history of Denmark. A third important source, not discovered until the seventeenth century, is the anonymous manuscript Codex Regius, commonly referred to as the “Poetic Edda.”

In that ancient mythological world, skating was not a recreational activity but a practical means of movement over ice and snow during the long Scandinavian winters, a necessity for travel and hunting. The implements employed were not ice skates in the modern sense. Most were closer in use and construction to snowshoes or skis. Animal bones or blocks of wood were fastened to the traveler’s feet, and staffs or poles were employed to push themselves across the ice or snow.

We know little of skating’s most ancient practitioner Ull, the god of snowshoes, of the shield, of the bow, of hunting, and for a time of security and law. He was reported to be fair to look at and a mighty hunter. His importance in the world of the gods is acknowledged by all scholars. The meaning of his name is debated, but one leading theory suggests that it relates to glory or brilliance. On his snowshoes, Ull represented the brilliance of the winter sky. In one account, he crossed the sea on a magic bone, clearly referring to the earliest kind of ice skates. Skating across lakes would have been an appropriate activity for an important deity of the North. As a chief god, Ull appears frequently in myths, but his eminence is most clear from one specifically about him. Saxo tells us that Ull replaced Odin, who as a chief god had been disgraced by disguising himself as a woman in order to beget an avenger. Ull reigned in Odin’s absence for ten years, even taking his name, but the gods eventually took pity on Odin and restored him to power. Ull fled to Sweden, where he was killed by the Danes.

Also important is Skadi, the goddess of snowshoes. Snorri reports that she traveled on snowshoes, used a bow, and hunted animals. She was probably also a goddess of winter and thus of darkness and death. What is confirmed by the myths is that in the ancient world movement over ice or snow was necessary for survival, and primitive forms of skates, snowshoes, and sledges were used for that purpose. But by the time these myths were recounted in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, skating had become a recreational activity and a sport in England and probably elsewhere.

The Earliest Skates

Skates are known to have been in use more than three thousand years ago. Made from the leg bones of large animals, including horses, deer, and sheep, they were filed and shaped to create a smooth surface throughout their length. They were not sharpened, thus having no edge like a modern skate. Holes were drilled in the bones so straps could be employed for fastening them to the skater’s shoes. Bone skates have been found in various European countries, including Denmark, England, Holland, Norway, and Sweden, and are on display in many museums.

These primitive skates facilitated movement quickly and efficiently across ice. Both feet were kept on the surface, and poles were used for pushing. Because the bones were not sharpened, skaters could neither push off nor maintain forward motion in the modern way. This was proven by an experiment undertaken in the 1890s by G. Herbert Fowler, a member of the London Skating Club, who constructed a pair of bone skates modeled exactly on a pair from the Guildhall Museum and confirmed by skating on them that it was not possible to “strike off” using the side of the bone. He did discover that it was possible to propel himself forward using the toe of the bone, which could bite the ice, but historical evidence suggests that staffs or poles were always employed for propulsion until the development of the bladed skate.4Close

Bone skates date back at least three thousand years, but other bone and stone implements were in use as much as ten thousand years ago in the same areas of Europe associated with the earliest skates. It seems probable that when hunting implements were being made, arrows were being shaped, and bone was being crafted into various tools, man would have discovered that by tying bones to his feet he could move efficiently across the ice, aiding in the hunt. Thus, the use of skates could have begun thousands of years earlier than can presently be documented.

The earliest known iron skates date from about 200 a.d. They were not sharpened but were strips of iron that functioned in the same manner as bone. The early iron runners may seem to have been an improvement, but they did not replace bone. Peasants would not have had the means of securing iron; bone was free. Iron runners provided no apparent advancement and probably no advantage to the art of skating. Skates continued to be made of bone throughout most of the Middle Ages, but sometime before the fourteenth century the Dutch revolutionized skating by employing sharpened steel blades. With that development, skating began its evolution into those sports associated with it today.

An Early Account of Recreational Skating

Although skating served first as a means of travel, at an early date it must have served also as a recreational activity, particularly among young people. Animal bones were readily available to anyone who would take the time to shape them into a pair of skates. Recreational skating, that is, skating just for fun or as a game, could easily date back many centuries, but the earliest descriptive account, written by William Fitz Stephen, dates from 1180. Fitz Stephen’s extensive description of Norman London includes a major section devoted to various games and sports, arranged seasonally, beginning with those practiced during Carnival. Games and sports played by young men not yet vested with the belt of knighthood were always combative and often incorporated lances and shields. Skating was no exception. On Sundays and feast days the public would turn out in large numbers to watch and cheer on the youths who participated.

Skating is the last sport mentioned because the winter season precedes Carnival. To many, skating was simply sliding across the ice, but it became a game when those with the greatest skill and best balance tied bones to their feet and moved with great speed, pushing themselves along with steel-pointed poles. Fitz Stephen’s account confirms that skating in twelfth-century London was both a recreational activity and a sport:

When the great marsh that washes the Northern walls of the city is frozen, dense throngs of youths go forth to disport themselves upon the ice. Some gathering speed by a run, glide sidelong, with feet set well apart over a vast space of ice. Others make themselves seats of ice like millstones and are dragged along by a number who run before them holding hands. Sometimes they slip owing to the greatness of their speed and fall, every one of them, upon their faces. Others there are, more skilled to sport upon the ice, who fit to their feet the shinbones of beasts, lashing them between their ankles, and with iron-shod poles in their hands they strike ever and anon against the ice and are borne along swift as a bird in flight or a bolt shot from a mangonel. But sometimes two by agreement run one against the other from a great distance and, raising their poles, strike one another. One or both fall, not without bodily harm, since on falling they are borne a long way in opposite directions by the force of their own motion; and whenever the ice touches the head, it scrapes and skins it entirely. Often he that falls breaks shin or arm, if he fall upon it. But youth is an age greedy of renown, yearning for victory, and exercises itself in mimic battles that it may bear itself more boldly in true combats.5Close

Skating as a Tool of Warfare

Skates became a practical tool of warfare four centuries later. In 1572, during the Dutch revolt against Spain and the reign of terror suffered under the ruthless Duke of Alva, King Philip II’s chief minister to the Netherlands, the Dutch fleet was trapped in frozen water at Amsterdam. Attacking from land across the frozen sea, Spanish soldiers were forced to retreat when they discovered that the Dutch had chopped a mote around the ships. As the Spaniards retreated, Dutch musketeers on bladed skates surprised them by moving with the mobility skates provided. They routed and massacred their attackers, who wore clogs with spikes that provided stability but not quickness on the ice. Alva reportedly ordered seven thousand pairs of skates for his own troops, but no other known battle on skates ever occurred.

The Dutch Roll

The Dutch success in routing the Spanish resulted from maneuverability possible with bladed skates. It is not clear when bladed skates first appeared, but it was before the fourteenth century in the Netherlands. Countries further north were not as conducive to ice skating because frozen lakes there were often covered with thick blankets of snow, suitable for sledging, skiing, and snowshoeing but not for skating on blades. The Netherlands, however, experienced long spells of cold weather and much less snow. Numerous canals that provided primary routes of trade and communication from town to town remained frozen for extended periods during the winter months. With less snow, canals could easily be maintained for travel by skaters, and the Dutch employed skates for winter travel.

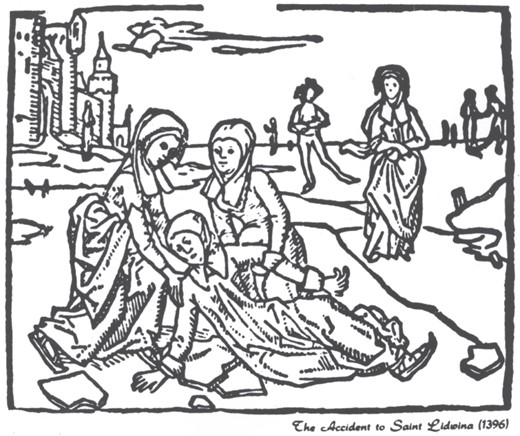

The introduction of sharpened blades changed the course of skating. Able to grip the ice, skaters no longer needed poles to push themselves along. They could use the edges of their bladed skates to push off as is done today, and continuous motion from foot to foot must have followed almost immediately. Discarding the poles had a practical side as well. The arms became free to carry items as skaters traveled from town to town. More important to the history of figure skating was the discovery of edges. At first skaters pushed and glided in a manner similar to what they had previously done with poles, but they must have soon discovered that by leaning to the left and right they could maintain a continuous and flowing motion that was both practical and artistic. The resulting edges, probably inside at first, provided great speed and physical beauty. This continuous movement, known as the Dutch roll, was clearly defined by the sixteenth century, but iconographic evidence supports skating on edges at least a century earlier. A famous late-fifteenth-century woodcut of St. Lydwina’s accident shows a skater approaching her who appears to be skating on an inside edge.6Close

The Dutch developed edges, inside and outside, the first figure skating moves and the basis of all figure skating. Compulsory figures and, with specific exceptions, virtually all free skating and dance moves are done on edges. Similar movement was just as necessary for the development of speed skating, and it was in speed skating, not figure skating, that the Dutch excelled during the ensuing centuries. The English became the first dominant force in figure skating, beginning with the introduction of the Dutch roll in the mid seventeenth century and continuing with figures derived from it, figures that would eventually give the sport its name.

Skating’s Patron Saint

It is appropriate to conclude this first chapter with a brief description of figure skating’s patron saint, the virgin Lydwina of Schiedam. Lydwina is remembered for a life of suffering that resulted from a skating accident. Born on Palm Sunday 1380, she was the only daughter in a poor family of nine children. By age fifteen she had become a vivacious and beautiful young lady. During the winter of 1395–96, while skating with friends on a frozen canal, Lydwina collided with another skater and broke a rib as she fell to the ice. Although she received the best medical care available, she never recovered. In fact, she grew steadily worse, not just in the short term but throughout her life, which lasted

Johannes Brugman’s fifteenth-century woodcut The Accident to St. Lidwina.

nearly thirty-eight more years. She died on Holy Tuesday in the year 1433. Within a year after the accident she suffered unexpected reactions as spasms of pain convulsed and contorted her body and she lost almost all muscular control of her limbs. Symptoms of various diseases appeared, and she was permanently bedridden. None of her former beauty remained.

Lydwina was ministered to by a priest from the local church, Father John Pot, who urged her to think always of the suffering of the lord and to relate her suffering to his. Constantly meditating on the Passion, she grew to believe that God had called on her to be a victim for the sins of others. About 1407 she began to have mystical visions, communing with God, various saints, and her guardian angel. Unable to eat solid foods, she subsisted on a liquid diet, and for the last seven years of her life she rarely slept. After her death a hospital was built on the site of the home where she had spent her years of suffering.

Modern knowledge of Lydwina comes from two early biographers, one her cousin, John Gerlac, and another by no less a writer than Thomas à Kempis. Although she is referred to as Saint Lydwina, she has never been officially canonized by the Church, but in 1890 her cult was formally confirmed by Pope Leo XIII. That year marked the beginning of a decisive decade of international importance in the history of figure skating. A major international competition was held in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1890, The first European Championship was held in 1891, the International Skating Union was founded in 1892, and the first World Championship was held in 1896. It is appropriate that the cult of the remarkable Lydwina was recognized at the time figure skating entered its modern and international period.

Quoted from the videocassette Magic Memories on Ice 2.

This was by an ISU regulation, however, by special dispensation; the free-skating portion of the World Championships the following year in Vienna was held on the outdoor rink of the Wiener Eislauf-Verein (Vienna Skating Club).

Quoted from the videocassette Magic Memories on Ice.

The woodcut is by the Dutch artist Johannes Brugman (1400–1473).

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| March 2023 | 1 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| January 2024 | 1 |

| February 2024 | 2 |